Last weekend Anette and I traveled to Idodi, 90km northwest of Iringa and 20km outside Ruaha National Park, where Anette helped facilitate a head teacher’s meeting for Friends of Ruaha Society at Idodi Secondary School. In a Land Rover the trip takes about an hour and a half, but I went by the only public bus that serves the villages near Ruaha and it took me five hours.

It was the worst bus I’ve yet been on in Africa – listing heavily to one side, holes rusted in the floor to give you a good view of the road beneath your feet, every window shattered like broken ice on a shallow pond. The window in my row of seats was half knocked out, the remaining glass turned inwards and barely hanging on, threatening to fall on and slice the next passenger. Large pieces of glass were scattered all over the floor of the bus, which had not been cleaned out in years.

First we waited at the bus station for a half an hour as the engine roared and smoked and I watched the rain slant through my broken window and soak the seat next to me. Then we started moving, but it was only to drive 20 meters back into town to a gas station, where it took us a half hour to fill up our 100-liter tank. As we waited, I watched a young man fill an old container with petrol and tie it fastidiously to the frame of his bicycle, and I wondered what would happen if he were to fall off his bike.

Finally the tank was full and off we drove, but alas, it was back the 20 meters we had just driven to stop for more passengers to cram themselves in like sardines. I couldn’t help but laugh out loud as I realized that after an hour we had gone in a 40-meter circle and were no closer to our destination. But such is African transport, and I was happy to be going out to Idodi.

The road is paved until about 15km outside of Iringa, and then it gets rocky and sandy, which is the rainy season means rocky and muddy. After two hours of being bounced around I was positive I couldn’t hold my bladder in such conditions any longer, and I prayed that we would get stuck so I would have a chance to get out and pee. My prayers were answered, for soon thereafter we heard a CLUNK and felt the whole bus grind to a halt. Sure enough, we were stuck in the mud and I was overjoyed. I navigated my way down the aisle over 50kg bags of maize flour (used to make the Tanzanian staple ugali) and plastic bags bursting with tomatoes and onions sold by side of the road vendors, and I leapt into the bush to relieve myself.

The driver and his crew were obviously prepared for such delays because they immediately broke out the shovels and began digging away to level the mud underneath the giant bald tires of the bus. After about ten minutes half the passengers got behind the bus and began pushing as the driver revved the engine. Slowly the bus lurched over the humps of mud and with the passengers jogging alongside we made it to drier ground.

At another one of our unplanned stops I saw two hands grab onto a window from the outside, and then watched as a man hoisted himself onto the roof of the bus. A bicycle was then lifted up to him and we took off down the road. I forgot all about him until about fifteen minutes later when the emergency hatch opened and suddenly two legs were dangling above my head - the guy jumped down from the roof, through the hatch and into the bus at speed!

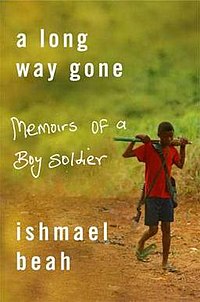

My only regret is that I did not have our camera with me, so I will have to keep the images of rainy, muddy Iringa as seen through a jagged windowpane in my head until our next bus adventure. For those who know Spanish, this picture of another bus will provide some laughs - the "super ugly" express!